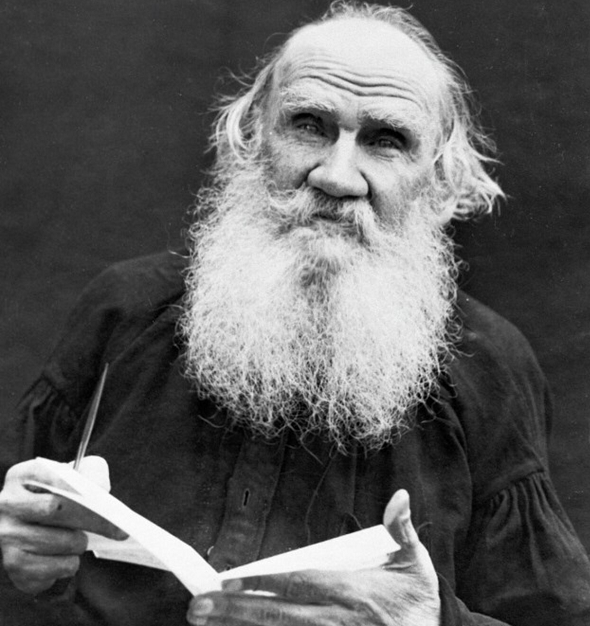

September 9, 1828 - November 20, 1910

Virginia Woolf once called Leo Tolstoy "the greatest of all novelists."

Through both his writing and his life, Tolstoy became known as a troubled man who devoted himself to the search for life's meaning. He's best known for penning the lengthy "War and Peace" and "Anna Karenina."

So how did a Book of Mormon end up in the library of this Russian literary leviathan?

Frederick and Nataliya Felt were attending the Laurel Ward of the Silver Springs Stake in Washington, D.C., when a Russian member told them that Tolstoy's library contained a copy of the LDS scripture.

Their initial intrigue turned into a quest to discover the story of its origin.

"I was surprised to learn that Tolstoy had a Book of Mormon," Frederick said. "I wondered how (he had obtained it) since the church didn't have missionaries in Russia during his lifetime."

Frederick determined there had to be some kind of inscription on the inside cover and that the information was a "valuable fragment of church history."

Nataliya had a personal interest. She was born in Moscow and knows both the language and the country's rich literary history.

"I knew and respected Tolstoy's works before I joined (the church)," Nataliya said. "I was really happy to know such a talented writer took an interest in the church."

They learned the book was at Yasnaya Polyana, the late author's estate, which is four hours south of Moscow by train. On a partly cloudy day last August, the Felts traveled to Yasnaya Polyana, now a museum operated by the Tolstoy family.

Like stepping back in time, the picturesque, sprawling estate consisted of "fields, forests, barns, apple orchards, stables, servant's quarters and several residences," Frederick said.

A librarian at the museum searched her records and photocopied a catalog reference to the Book of Mormon.

"It identified the exact cabinet, shelf and volume number," Frederick said.

More importantly, the reference indicated that the book was a gift given to Tolstoy by Susa Young Gates, daughter of Brigham Young, women's rights advocate and a writer once referred to by R. Paul Cracroft as "the most versatile and prolific LDS writer ever to take up the pen in defense of her religion."

During her lifetime, Gates carried on intellectual correspondence with Tolstoy, William Dean Howells, Charlotte Perkins Gilman and other prominent literary figures. English Ph.D. Lisa Tait, who has presented at the BYU Studies Symposium on Gates and is currently working on her biography, said she would not be surprised if Gates, as an afficionada of classic literature, got in contact with Tolstoy on impulse.

"Knowing her and her amazing self-assurance, she probably just wrote a letter to him cold," Tait said.

The Felts were eager to see Gates' inscription in the Book of Mormon, but discovered that the museum director, who would have to authorize them to look at or photograph Tolstoy's books, was out of town.

"The secretary invited us to submit a written request for the director's consideration," Felt said. "But when we explained our time constraints, she made a call."

An assistant director approved the Felts' request. The museum curator took them into Tolstoy's office where they pulled on white gloves and were handed Tolstoy's Book of Mormon.

"It was surprisingly heavy," Frederick said. He identified the copy as an 1881 Second Electrotype Edition published in Liverpool, England.

Gates' inscription simply read: "Count Leo Tolstoy, from Susa Young Gates. Salt Lake City, Utah."

He noted that other than the inscription, there were no other notes on any of the pages.

The curator helped the Felts consult Tolstoy's diary, where they found an entry mentioning that he had received the book from Gates and had "read the book."

"Whether Tolstoy meant that he had read the book in its entirety or only in part wasn't clear from the entry," Frederick said.

The Felts took several photographs of both the book itself and the diary page. Upon returning home, digital enhancement of some of the photos showed possible acid marks from fingerprints on the Book of Mormon's title page, "suggesting Tolstoy had paused there to read," Frederick said.

After Tolstoy wrote "Anna Karenina," he experienced intense existential despair and found himself impressed with the faith and devotion of the religious laypeople.

His interest gravitated toward the religion he was born into, the Russian Orthodox church, but he soon abandoned it, convinced that all Christian churches had corrupted Christ's message.

In the same vein, Tolstoy abhorred the persecution of others for their religious beliefs or interpretations of Christianity. He used the royalties of his 1899 novel "Resurrection" to pay for the transportation of a persecuted religious sect, the Dukhobors, to Canada.

Tait pointed out the Christian socialist movement in the late 1800s and how some Mormons felt there were affinities between LDS beliefs, such as the law of consecration, and pre-Communist era socialist ideas.

"It may have been in that vein that Gates contacted Tolstoy," Tait said.

In 1995, Lawrence R. Flake, then an associate professor in the department of church history and doctrine at BYU, gave a devotional address which detailed a conversation Tolstoy had with Andrew Dixon White, co-founder of Cornell University.

Tolstoy was said to have told White: "If Mormonism is able to endure, unmodified, until it reaches the third and fourth generation, it is destined to become the greatest power the world has ever known." While the accuracy of this story cannot be verified, Tolstoy did nurture a lifelong fascination with and rare respect for Mormonism as he struggled with religion and the desire to see all allowed freedom of worship.

Through both his writing and his life, Tolstoy became known as a troubled man who devoted himself to the search for life's meaning. He's best known for penning the lengthy "War and Peace" and "Anna Karenina."

So how did a Book of Mormon end up in the library of this Russian literary leviathan?

Frederick and Nataliya Felt were attending the Laurel Ward of the Silver Springs Stake in Washington, D.C., when a Russian member told them that Tolstoy's library contained a copy of the LDS scripture.

Their initial intrigue turned into a quest to discover the story of its origin.

"I was surprised to learn that Tolstoy had a Book of Mormon," Frederick said. "I wondered how (he had obtained it) since the church didn't have missionaries in Russia during his lifetime."

Frederick determined there had to be some kind of inscription on the inside cover and that the information was a "valuable fragment of church history."

Nataliya had a personal interest. She was born in Moscow and knows both the language and the country's rich literary history.

"I knew and respected Tolstoy's works before I joined (the church)," Nataliya said. "I was really happy to know such a talented writer took an interest in the church."

They learned the book was at Yasnaya Polyana, the late author's estate, which is four hours south of Moscow by train. On a partly cloudy day last August, the Felts traveled to Yasnaya Polyana, now a museum operated by the Tolstoy family.

Like stepping back in time, the picturesque, sprawling estate consisted of "fields, forests, barns, apple orchards, stables, servant's quarters and several residences," Frederick said.

A librarian at the museum searched her records and photocopied a catalog reference to the Book of Mormon.

"It identified the exact cabinet, shelf and volume number," Frederick said.

More importantly, the reference indicated that the book was a gift given to Tolstoy by Susa Young Gates, daughter of Brigham Young, women's rights advocate and a writer once referred to by R. Paul Cracroft as "the most versatile and prolific LDS writer ever to take up the pen in defense of her religion."

During her lifetime, Gates carried on intellectual correspondence with Tolstoy, William Dean Howells, Charlotte Perkins Gilman and other prominent literary figures. English Ph.D. Lisa Tait, who has presented at the BYU Studies Symposium on Gates and is currently working on her biography, said she would not be surprised if Gates, as an afficionada of classic literature, got in contact with Tolstoy on impulse.

"Knowing her and her amazing self-assurance, she probably just wrote a letter to him cold," Tait said.

The Felts were eager to see Gates' inscription in the Book of Mormon, but discovered that the museum director, who would have to authorize them to look at or photograph Tolstoy's books, was out of town.

"The secretary invited us to submit a written request for the director's consideration," Felt said. "But when we explained our time constraints, she made a call."

An assistant director approved the Felts' request. The museum curator took them into Tolstoy's office where they pulled on white gloves and were handed Tolstoy's Book of Mormon.

"It was surprisingly heavy," Frederick said. He identified the copy as an 1881 Second Electrotype Edition published in Liverpool, England.

Gates' inscription simply read: "Count Leo Tolstoy, from Susa Young Gates. Salt Lake City, Utah."

He noted that other than the inscription, there were no other notes on any of the pages.

The curator helped the Felts consult Tolstoy's diary, where they found an entry mentioning that he had received the book from Gates and had "read the book."

"Whether Tolstoy meant that he had read the book in its entirety or only in part wasn't clear from the entry," Frederick said.

The Felts took several photographs of both the book itself and the diary page. Upon returning home, digital enhancement of some of the photos showed possible acid marks from fingerprints on the Book of Mormon's title page, "suggesting Tolstoy had paused there to read," Frederick said.

After Tolstoy wrote "Anna Karenina," he experienced intense existential despair and found himself impressed with the faith and devotion of the religious laypeople.

His interest gravitated toward the religion he was born into, the Russian Orthodox church, but he soon abandoned it, convinced that all Christian churches had corrupted Christ's message.

In the same vein, Tolstoy abhorred the persecution of others for their religious beliefs or interpretations of Christianity. He used the royalties of his 1899 novel "Resurrection" to pay for the transportation of a persecuted religious sect, the Dukhobors, to Canada.

Tait pointed out the Christian socialist movement in the late 1800s and how some Mormons felt there were affinities between LDS beliefs, such as the law of consecration, and pre-Communist era socialist ideas.

"It may have been in that vein that Gates contacted Tolstoy," Tait said.

In 1995, Lawrence R. Flake, then an associate professor in the department of church history and doctrine at BYU, gave a devotional address which detailed a conversation Tolstoy had with Andrew Dixon White, co-founder of Cornell University.

Tolstoy was said to have told White: "If Mormonism is able to endure, unmodified, until it reaches the third and fourth generation, it is destined to become the greatest power the world has ever known." While the accuracy of this story cannot be verified, Tolstoy did nurture a lifelong fascination with and rare respect for Mormonism as he struggled with religion and the desire to see all allowed freedom of worship.

No comments:

Post a Comment